Two years on from Turkey earthquakes: Who is the Antakya protection plan protecting?

Known as "the world's first illuminated street," Kurtuluş Street runs through the heart of Antakya's historic city center. In Roman times, it was called the Colonnaded Street or Herod’s Road, and during the French Mandate (1920–1939), it was referred to as "Rue Jadid" (New Street). However, following the February 6 earthquakes, the two-kilometer-long street has been left in darkness.

As the second anniversary of the earthquake approaches, the historic neighborhoods flanking the street continue to struggle with uncertainty regarding both reconstruction and demolition amidst the ruins.

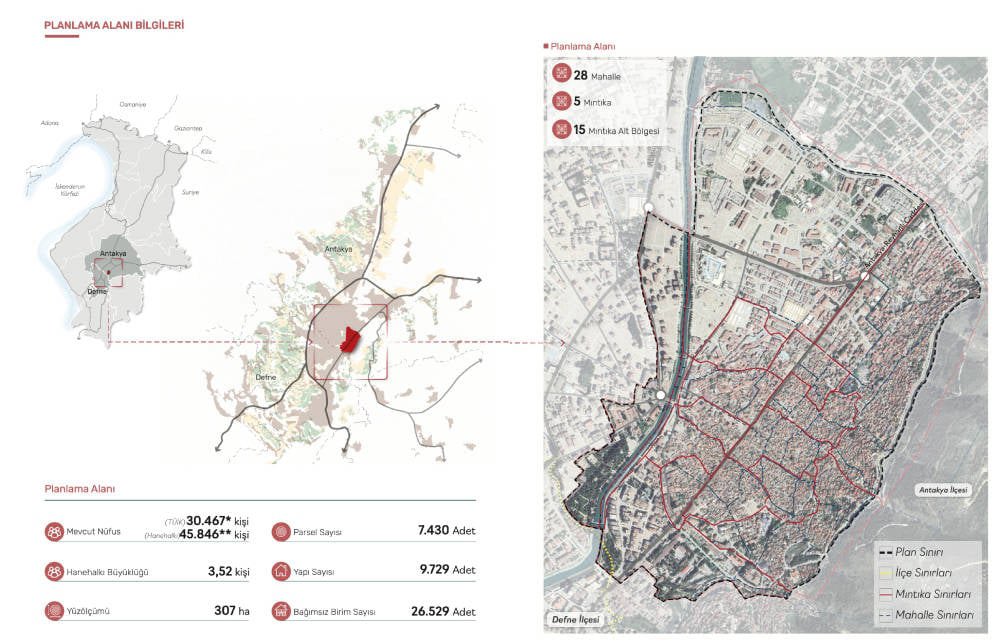

The area historically known as Affan—officially called Fevzi Çakmak Neighborhood—spans a larger area encompassing both sides of the street. It also includes parts of Gazipaşa, Kuyu, Güllübahçe, and Zenginler neighborhoods.

Before the earthquake, Affan was characterized by "old Antakya houses," featuring courtyards, small decorative pools, and gardens. It was a neighborhood where Arabs, Turks, Alevis, Sunnis, Armenians, Jews, and Christians lived together—what Fevzi Çakmak Neighborhood's headman, Şefik Fatihoğlu, described as a true "mosaic" of Antakya.

The earthquake inflicted severe damage on the neighborhood, and even structures that remain undamaged or lightly damaged are now under threat.

'Residents can’t get clear answers'

Before the earthquake, around 500 households, comprising over 4,000 residents, lived in the neighborhood, according to Fatihoğlu. He now doesn't know the exact number of current residents but noted that multiple families are sharing undamaged or lightly damaged homes.

Fatihoğlu explained that while displaced residents cannot return due to uncertainty about rebuilding, those living in undamaged or lightly damaged homes fear that their houses might still be demolished.

In an interview with bianet, Fatihoğlu said, “Due to the conservation plan, residents cannot obtain construction permits. I asked the Deputy Mayor of Antakya about this issue, and he told me, ‘The [Ministry of Environment, Urbanization, and Climate Change] will merge the parcels here. We cannot issue permits until this process is complete.’”

According to Fatihoğlu, ministry teams have inspected the neighborhood and verified undamaged and lightly damaged buildings. However, officials have reassured residents by saying, "Don’t worry, everyone here will have ownership rights," which has only raised more concerns.

Fatihoğlu emphasized that these developments have heightened fears of widespread demolition. He added, “Our residents are not receiving clear answers and have started to create their own narratives about what might happen.”

Living in the middle of ruins

Some of the registered historical buildings along Kurtuluş Street are surrounded by banners marked "Ministry of Culture and Tourism." In other parts of the neighborhood, similar buildings are labeled only with the word "Registered."

Where once narrow streets lined with closely packed houses stood, there is now a vast emptiness. In the middle of this emptiness, a few buildings labeled "Undamaged" or "Under Legal Dispute" stand out. In these undamaged homes, multiple families are forced to live together under difficult conditions.

Sixty-five-year-old Feyruz Accan, who lives in a two-story house with three families and a total of nine people, expressed her strong attachment to the area: “I was born here, I grew up here, and I want to die here.”

Accan explained that her house was not damaged in the earthquake and that she managed to handle small repairs on her own: “If our house is demolished, where will we go? How can we all find a place to live? The children don’t have homes. We have no idea what we’ll do.”

The situation is no different for those living in undamaged or lightly damaged apartment buildings.

Seventy-six-year-old Nezahat K., whom we met at the only functioning bakery in Affan, invited us to her home, a few hundred meters away, to show us the lightly damaged building under demolition threat and to raise awareness with her neighbors.

When cracks on the exterior of the five-story building caught our attention, Nezahat K. explained, “Because of the uncertainty, we don’t want to invest in repairs.”

We visited Nezahat K. and her downstairs neighbor, 74-year-old Nadiye P., who also lives alone. Both women, who rely on their retirement pensions, described their struggles:

“We can’t sleep at night because of the stress. Haven’t we suffered enough? We have nowhere else to go.”

The situation has also affected local business owners, including shopkeepers, bakers, café owners, and pharmacists.

Pharmacist Haydar Temiz reopened his shop on Kurtuluş Street four months after the earthquake and has been operating since May 15, 2023.

Temiz, who served as the area’s only pharmacist for an extended period, explained that the building his pharmacy is located in is now facing demolition: “While we were already struggling with so many challenges, about a month and a half ago, Kurtuluş Street was declared a ‘reserve area,’ and a demolition notice was posted on our window.”

Temiz noted that the three-story building is undamaged and that the upper floors are used as residences. They are currently waiting for the results of a core sample test requested by the property owner to contest the demolition order. He added:

“Where are we supposed to go if we’re forced to vacate? If they had told us from the beginning, ‘You can’t open a pharmacy here,’ we wouldn’t have done it. But they didn’t, and now we can’t find anyone to speak to. Are they trying to make us abandon the area?”

'This uncertainty must end'

Despite promises that the area’s cultural and demographic structure would be preserved, residents remain anxious. Headman Şefik Fatihoğlu made a direct appeal to the authorities:

“Our demand is simple: we want a decision about the future of our neighborhood and for residents to be informed. My phone doesn’t stop ringing 24/7. People are influenced by every rumor they hear and constantly contact us to verify information and ease their worries. This uncertainty needs to end.”

'A complex and opaque process'

Urban planner Ceyhan Çılğın told bianet that no effort has been made to understand how Antakya’s residents wish to live in the area, nor have ownership criteria been clarified, which has led to significant uncertainty in the region.

Çılgın criticized the Ministry of Environment, Urbanization, and Climate Change for leaving residents without clear communication and running a process that is both difficult to monitor and overly complicated. He further explained:

“On the other hand, areas across the Asi River have been declared reserve zones. However, no cohesive plan has been established between the risky area and these reserve zones. This is, after all, a designated urban conservation site. It’s a place that should be interconnected and thought of in relation to other areas. Yet on the other side, various Emlak Konut and TOKİ projects have turned the area into a chaotic construction site driven by haphazard tenders.”

(VC/VK)

Forced land seizure in Hatay: 'We survived the earthquake, but the government is killing us'

Erdoğan shows protest footage from Georgia in speech targeting İmamoğlu protests

WITNESSES OF THE SAHEL MASSACRE

Zaynab from Latakia: We just want to live in security and peace

ANNIVERSARY OF FEB 6 QUAKES

The never-ending 'temporary' life in a Hatay tent city

Turkey’s last Armenian village faces expropriation threat